The SB908 report can be downloaded as PDF files to be read with the Acrobat Reader, and its maps viewed as graphics (JPG) files. Alternatively, a detailed synopsis, containing many excerpts from the report, follows below.

Background

In late 2001, the California State Legislature, by way of SB 908, directed the State Coastal Conservancy to determine what is needed to complete the Coastal Trail. The ensuing report was completed in early 2003. Titled “Completing the California Coastal Trail”, it was prepared by Conservancy staff with the participation of the Coastal Commission and State Parks, plus staff and volunteers from Coastwalk. Those directly involved, “The Working Group”, chaired by Conservancy Deputy Executive Officer Steve Horn, met monthly for more than a year. The intent of the SB908 report was summarized in the report’s letter of conveyance, written by Sam Schuchat, Executive Officer of the California State Coastal Conservancy:

…I believe that continuing investment in public access to California’s coastline and parks is essential to maintain and improve our quality of life. As the State’s population continues to grow, more recreational facilities will be needed; well-designed hiking, biking and equestrian trails provide urban residents with opportunities to enjoy nature without imperiling sensitive habitat areas…

…The California Coastal Trail is a concept that has captured the imagination of public officials at all levels of government. Inherent in a project of this scope, substantial physical and administrative obstacles lie ahead; we look forward to working with our State, local and federal partners and the private sector to meet these challenges. In doing so, the support that this project has received from local community groups should be rewarded with an implementation program that reflects the highest quality of design and environmental protection…

History of the Coastal Trail

The report provides a brief history of the Coastal Trail:

The coast of California has been used as a trail for as long as people have inhabited the land. Native tribes residing near the coast on a permanent or seasonal basis used the readily-accessible beaches and coastal grassland bluffs as a transportation and trading route, and many subsequent visitors have trod those same paths.

The Portola expedition in 1769 marked the first overland journey by Europeans along the California coast. This was followed a few years later by the de Anza expeditions. This latter effort is now commemorated by the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, which shares part of its route with the Coastal Trail. In 1910 and 1911, J. Smeaton Chase explored the California coast by horseback. His record of this journey, published as California Coast Trails, describes the pleasure of traveling “within sight of the sea and within sound of its wise, admonitory voice.” More recently, in 1996, a determined band from the nonprofit group Coastwalk hiked the entire California coast to demonstrate that it was possible to do so despite many impediments. In 2003, Coastwalk members repeated their prior feat, again hiking the whole coast from Oregon to Mexico. Visit the CTE 2003 journal.

Policy makers and coastal managers have long planned for a continuous coastal trail in California. The Coastal Act of 1976 required local jurisdictions to identify an alignment for the California Coastal Trail in their Local Coastal Programs. Proposition 20, 1972, provides that “A hiking, bicycle, and equestrian trails system shall be established along or near the coast” and that “ideally the trails system should be continuous and located near the shoreline.”

The California Coastal Trail was designated California’s Millennium Legacy Trail in 1999 by Governor Davis and the White House Millennium Council, encouraging federal agencies to assist in developing it. State legislation in 2001 aimed at a focused effort to complete the Coastal Trail. Assembly Concurrent Resolution 20 (Pavley) declares the Coastal Trail an official state trail and urges the Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy to work collaboratively to complete it. Senate Bill 908 (Chesbro) charges the Coastal Conservancy, in cooperation with the Coastal Commission and State Parks Department, to submit to the Legislature a plan that describes how the Coastal Trail may be completed by 2008.

What will the trail be like and how will it be built

After considerable discussion and consideration of prior descriptions of the Coastal Trail in legislative documents, the Working Group agreed on this definition of the California Coastal Trail:

A continuous public right-of-way along the California coastline; a trail designed to foster appreciation and stewardship of the scenic and natural resources of the coast through hiking and other complementary modes of non-motorized transportation.

In addition, a broader set of objectives were drawn for the Coastal Trail Project:

1. Provide a continuous trail as close to the ocean as possible, with vertical access connections at appropriate intervals and sufficient transportation access to encourage public use.

2. Foster cooperation between State, local and federal public agencies in the planning, design, signing and implementation of the Coastal Trail.

3. Increase public awareness of the costs and benefits associated with completion of the Coastal Trail.

4. Assure that the location and design of the Coastal Trail is consistent with the policies of the California Coastal Act and local coastal programs, and is respectful of the rights of private landowners.

5. Design the California Coastal Trail to provide a valuable experience for the user by protecting the natural environment and cultural resources while providing public access to beaches, scenic vistas, wildlife viewing areas, recreational or interpretive facilities and other points of interest.

6. Create linkages to other trail systems and to units of the State Park system, and use the Coastal Trail system to increase accessibility to coastal resources from urban population centers.

From vision to working guidelines

In the course of preparing the SB 908 report, individuals from several advocacy groups were invited to submit statements as to their vision for the Coastal Trail. Here are three responses, from Coastwalk, the California Bicycle Coalition and the Santa Monica Mountains Trail Council:

WHAT SHOULD THE COASTAL TRAIL BE?

Richard Nichols, Executive Director, CoastwalkPassage of SB 908, the Coastal Trail bill, was preceded by almost 20 years of advocacy by Coastwalk. … The task of Coastwalk, a nonprofit citizens’ organization, has been to educate the public, elected officials and state agencies in the values and benefits of a continuous trail along the state’s entire shoreline.

Hikers find inspiration and pleasure in walking a simple path along an interesting route. Coastwalk envisions a 1,300-mile hiking trail linking California’s northern and southern borders through one of the planet’s great landscapes; a trail that will extend along beaches, bluffs and roadsides, through ancient redwood forests, over sand dunes, mountains and cactus covered hillsides, through towns, cities, parks, and historic sites. Respecting and protecting the terrain, the California Coastal Trail will vary widely, according to the character of the landscape and the built environment. In many areas it will be a path for hikers and equestrians through wilderness and along beaches; in other areas it will be a paved, urban pathway, accessible to bicyclists, skaters, wheelchair riders and others using nonmotorized transportation. It will be a braided trail in many places, designed as a cohesive system to accommodate many people and different uses.

… The Coastal Trail will rival any long distance trail in the world for scenic beauty, diverse landscapes and interesting locations. … Whether strolling along the Venice Beach boardwalk or contemplating a sunset from a secluded beach on the north coast, people who use the trail will enjoy and respect this fragile and unforgettable coastline, and wish to conserve it for future generations.

…………………………………………………………………………….COASTAL BICYCLE TRAVEL

Chris Morfas, Executive Director, California Bicycle CoalitionWhile many trails provide useful recreational bicycling opportunities, cyclists traveling along the coast are best served by ensuring that roads accommodate them properly and that motorists are encouraged to share the road with them.

Recreational trails can serve families enjoying short bike rides as part of a car trip. Paved trails should meet Caltrans standards, so that bicyclists can safely share those facilities with joggers, skaters, parents with baby strollers, etc. Generally, unpaved trails can be enjoyed by both bicyclists and hikers if this dual use is expected and approached with courtesy by all. Signs indicating destinations, points of interest and approaching road intersections are very helpful.

Improving coastal roads to include bicyclists is challenging. While most urban streets or rural highways can usually be provided with a wide outside lane, bike lane or shoulder, efforts to widen coastal roads – – frequently located within or adjacent to sensitive natural areas – – can be enormously expensive and environmentally undesirable. Nevertheless, many sections of State Highway 101 and State Highway 1 could be made safer for bicyclists, and California can see some well-designed examples of how to do it along Highway 101 on the Oregon coast.

Perhaps the most cost-effective way to enhance coastal bicycle travel would be by modifying the behavior of motorists. … In most instances, as long as motorists are willing to slow for a few seconds to execute a safe pass, bicyclists and motorists can both safely enjoy the wondrous beauty that is the California coastal experience. For more information on this topic, you can reach the California Bicycle Coalition at www.calbike.org.

………………………………………………………………………………THE COASTAL TRAIL SHOULD INCLUDE EQUESTRIAN USES

Ruth Gerson, President, Santa Monica Mountains Trails CouncilEquestrian trails groups have been involved over many years in advocating for expanded opportunities for access to public lands. The equestrian community can support the proposed California Coastal Trail if all agencies concerned with designing and completing the trail will bear in mind and plan for the needs of horses and riders.

…To address the needs of equestrian users, the Coastal Trail should provide:

1. Ready access to the Coastal Trail from local feeder/connector trails, including wide dirt shoulders along local roads and roadway underpasses;

2. Trailhead parking that is a short distance from the trail and offers safe access to the trail;

3. Parking facilities that are large enough for truck and trailers, since equestrians cannot access the trail if they cannot park their rig;

4. Opportunities for overnight camping along the trail, so that users may fully enjoy the experience of sunrises and sunsets, marine vistas and wildlife, without having to drive their vehicles every day;

5. Trailheads that are not paved and are not excessively rocky or slippery;

6. A trail that is away from the sounds and dangers of roads and major highways as much as possible; and

7. Connections with other trails systems that have been designed to accommodate equestrian use, including the ones already recognized for their scenic and historic values such as the Juan de Anza Trail, the Santa Monica Mountains Backbone Trail, and the California Riding and Hiking Trail. …The Santa Monica Mountains Trails Council has been involved for 30 years with expanding public access in the Santa Monica Mountains…. We appreciate the opportunity to add the voice of the equestrian community to the effort to develop and maintain a public trail system along the California coast.

…………………………………………………………………………….

In addition, the Working Group considered the needs of individuals with disabilities:

The California Coastal Trail is a public facility and therefore must comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). The federal Access Board, the agency responsible for developing ADA accessibility standards, is currently working to develop guidelines for outdoor recreation facilities. The Access Board has had some difficulty in establishing ADA design guidelines for trails, especially in seeking to balance the need for man-made improvements to increase accessibility against the desire to maintain users preferred experience of many trails as “natural” features. …

In the absence of formal guidelines, new Coastal Trail segments should be designed to provide access to multiple users where topography permits that, and should provide information regarding the physical condition of the trail ahead. …

Finally, staff of the Coastal Commission, which is entrusted by law to assure public access to and along the shoreline, revisited and revised its planning guidelines for the Coastal Trail. Written by Lee Otter, Chief Planner of the Commission’s Central Coast District, and himself a frequent hiker and biker, and Linda Locklin, the statewide manager of the Commission’s access program, and an enthusiastic outdoors person, the policy reflects a broad and sympathetic view of how the trail will best serve and protect public interest.

THE FIVE PRINCIPLES FOR DESIGNING THE COASTAL TRAIL

Lee Otter, Central Coast District

Linda Locklin, Coastal Access Program

California Coastal CommissionThe Coastal Commission and local communities have been working since 1972 to increase public access to the shoreline. Many, many opinions have been expressed regarding the appropriate design of public access facilities, and many proposals have been put forward for the establishment of a single set of standards for public trails along the California coast. These suggested standards generally address such topics as trail width, surfacing, setbacks from the edge of the coastal bluff, trail furniture, signing, and necessary accommodations for the needs of various user groups. The topic that seems to stimulate the most heartfelt and animated discussions, however, is the trail alignment, namely, just where should the trail go?

To answer this question in regard to the Coastal Trail we must know what user groups will the trail be designed to accommodate: hikers? bicyclists? mountain bikes or road bikes? people in wheelchairs? equestrians? We must also consider seasonal variations, such as beaches narrowed in winter, for instance, nesting season for snowy plovers and least terns, and the elephant seal migration.

In the case of the Coastal Trail, existing development patterns or other constraints along some parts of the coast may dictate that more than one user mode will be obliged to share a single-trail alignment. But in areas that are subject to intensive use, experience has taught us that parallel tracks may be needed to accommodate different modes and to minimize conflicts. Experience has also shown us that if the trail to be accepted and supported in our coastal communities, it must be adapted to local circumstances and sensibilities. One size does not fit all, nor would any single standardized model work for the entire Coastal Trail.

Therefore the Coastal Trail will be comprised of many differing segments, each with its own character, reflecting the great diversity and variety found among our coastal communities. The trail also needs to be adaptable to environmental constraints, which may vary immensely over the course of a year. The challenge is to provide an orderly alignment to the trail system while at the same time allowing for community individuality. Thus, to assure a consistent high level of quality and connectivity throughout the length of the state, common principles are needed. To meet this need, and to provide a framework for the task of identifying the route of the trail, Coastal Commission staff has drafted a set of Coastal Trail alignment principles, based on shared values. These principles are: proximity to the sea, connectivity, integrity, respect, and feasibility. Each of these principles, explained below is based on the following premise:

The Basic Premise:

The Coastal Trail is not a single designated pathway spanning the length of California’s shoreline. It should be envisioned as a yarn comprised of several different but roughly parallel threads—here widely separated, there drawn together—with each thread being a particular trail alignment or trail improvement that responds to a specific need or accommodates a particular purpose. One thread may be for beach walkers, another for bicyclists, another may be merely an interim or temporary alignment, or may be placed where it is because of topography, land ownership or natural barrier. Some threads may be seasonal paths to detour around a snowy plover nesting site, circumvent a sprayed agricultural field, or bypass winter high water where a fast-flowing river cuts a barrier across the beach. Yet when we step back, we can see that all the threads form a coherent whole.

Five Specific principles for laying out the CCT are detailed in SB 908. Briefly quoted in the following, they apply to all of the different components trail:

► PROXIMITY. Wherever feasible, the Coastal Trail should be within sight, sound, or at least the scent of the sea.

► CONNECTIVITY. The trail should effectively link starting points to destinations. … Our challenge is to create non-automotive alternative connections that are sufficiently appealing to draw travelers out of their automobiles.

► INTEGRITY. The Coastal Trail should be continuous and not compromised by motor traffic. …

► RESPECT. The trail must be located and designed with a healthy regard for the protection of natural habitats, cultural and archaeological features, private property rights, neighborhoods, and agricultural operations along the way. …

Respect also requires understanding that this trail will exist in a context of other trail designations, including the Pacific Coast Bike Route, Humboldt Bay Trail, Lost Coast Trail, …Where the Coastal Trail alignment incorporates or is a component of these other trails, the Coastal Trail should be no more than a concurrent designation.

► FEASIBILITY. To achieve timely, tangible results with the resources that are available, both interim and long-term alignments of the Coastal Trail will need to be identified.

How much of the trail is complete, and how much will it cost to finish and maintain?

Some would say that the CCT will never be complete, but continually evolve in response to changes in coastal terrain and environment, and influenced by the availability of coastal public lands on which to route the trail. On the other hand, some still-functioning trails can be identified that have been in place for thousands of years, such as Rome’s Appian Way, where a visitor can tread on ancient cobbles. In fact, it is quite possible that trails established by California’s coastal Indians such as the Chumash trail in Pt. Mugu State Park are even older, perhaps exceeding 7,000 years of continuous use.

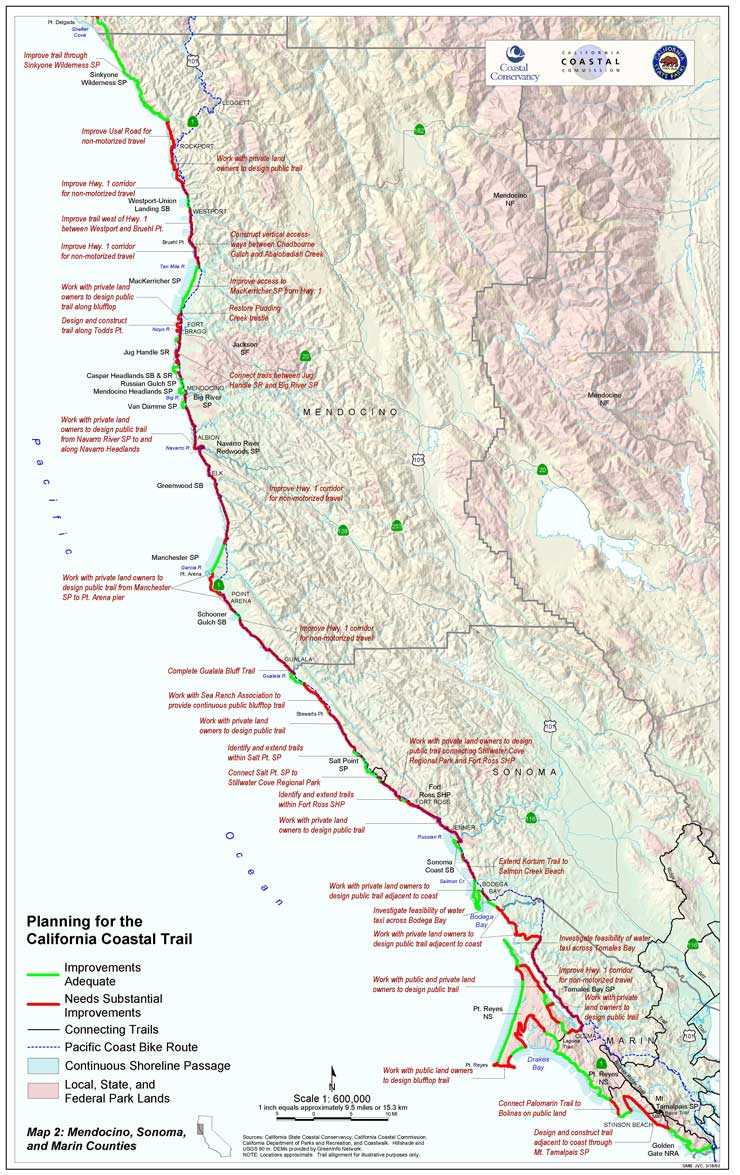

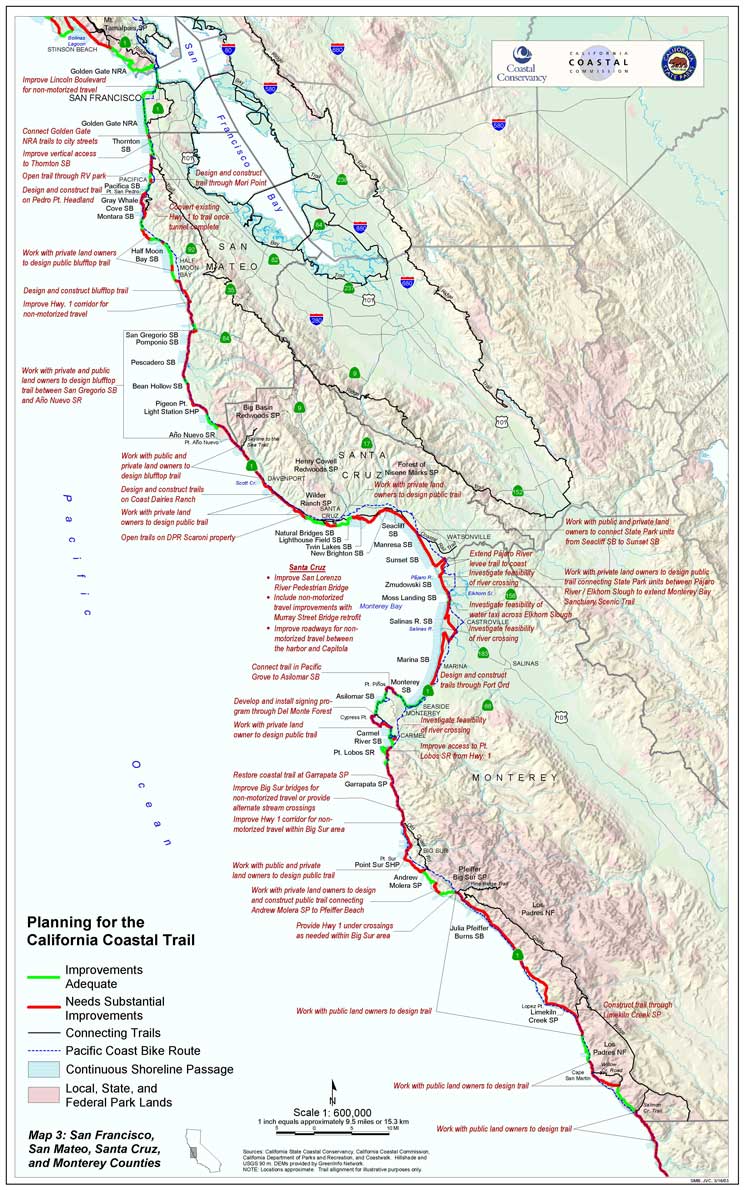

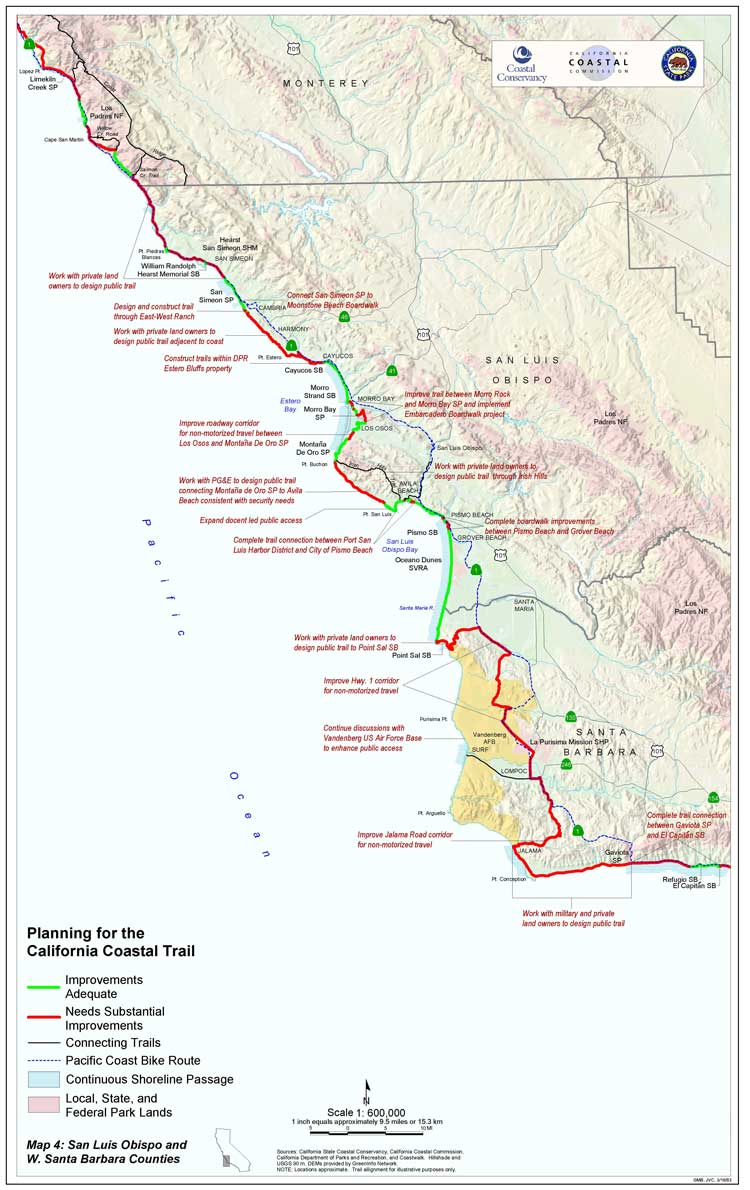

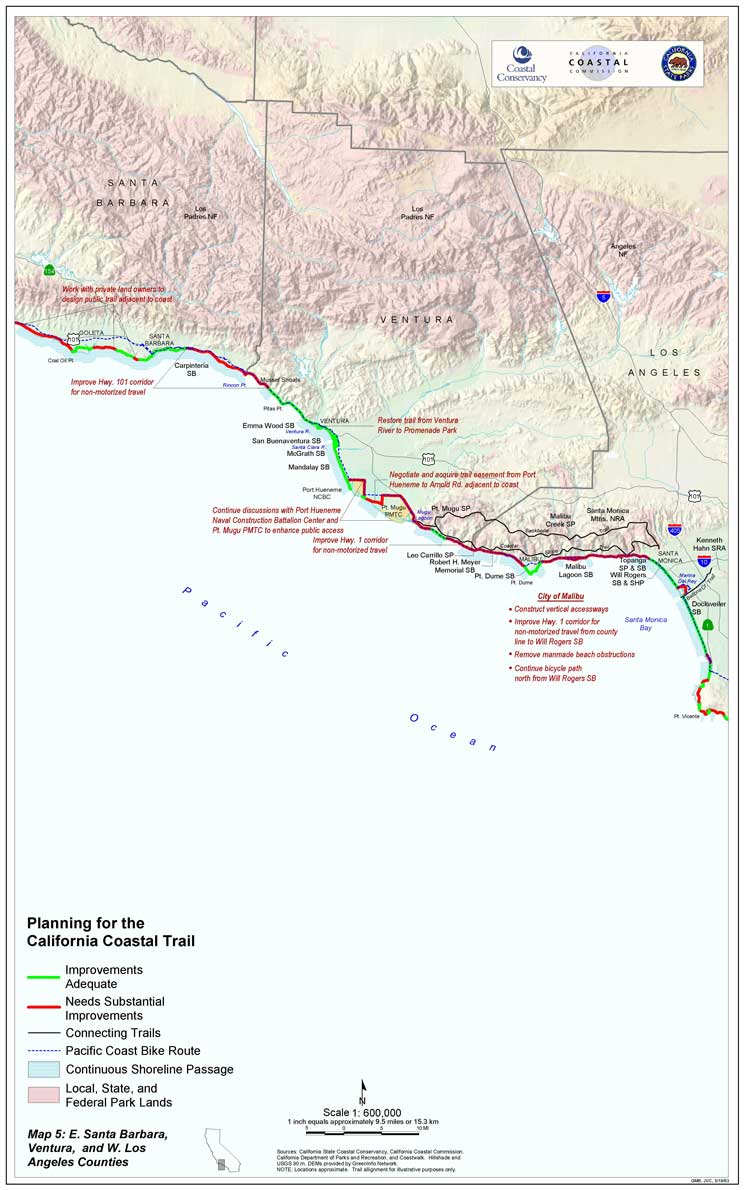

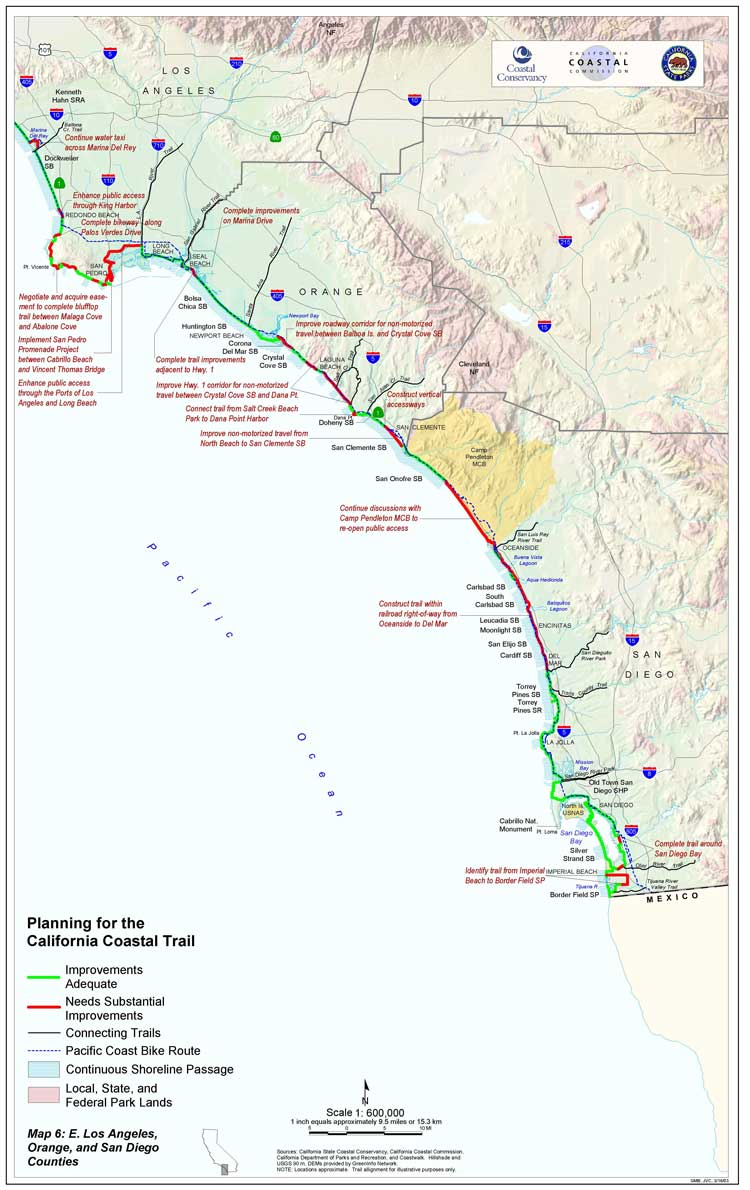

In this context, the SB 908 set a target date for completion of the trail in 2008. To determine how much of the trail was complete, Conservancy staff drew information about where the Coastal Trail runs from the Local Coastal Plans of communities along the coast and interviewed public officials in communities, counties, and National Parks as well as knowledgeable individuals and members of Coastwalk. They also considered the maps in the two volumes, “Hiking the California Coastal Trail” Lorentzen and Nichols; Bored Feet Press). The trail alignment on these maps is based on the routes taken by hikers during Coastwalk’s of the Coastal Trail. From this broad input, Conservancy staff and the technical services staff of the Coastal Commission prepared the maps accompanying the SB 908 report. In this process, segments of the trail were graded as adequate (or better) or needs substantial improvement (or worse). These maps were then further reviewed by the Working Group and regionally knowledgeable ad hoc volunteers, and finally field checked by Coastwalk volunteers up and down the state.

From this map information and the costs of past trail projects, the costs of completing the CCT and providing signage were estimated, as detailed in the following:

The California Coastal Trail will offer experiences that range from a stroll on the sandy beach to roller skating on a concrete esplanade, and from a horseback ride through deep forest to a hike along a barren bluff. To provide these public recreational experiences, a variety of financial commitments, including both one-time capital outlay—for acquisition of new rights-of-way, construction of a variety of trail surfaces, installation of directional and interpretive signs, improvements to numerous public highways, etc.—and for on-going expenditures for supervising public use of these facilities and planning for their maintenance and repair.

While the costs of specific trail improvement projects will vary from site to site, by comparison with the known costs of recent acquisition and trail improvement projects it is possible to provide a reliable estimate of the total capital outlay costs necessary to complete the Coastal Trail in accordance with the recommendations made in this report.

With such cost estimates and the number of miles within each county for which capital improvements would be required (as evaluated by the mapping data, shown in the table below), an estimate of the total expenditure needed in order to complete the trail was made.

| Improvements Needed to Complete the Coastal Trail: | ||||

| Estimated Linear Mileage by County | ||||

| County | Highway Corridor Improvements | Acquisition / Construction on Private Lands | Construction on Public Lands | Current Improvements Adequate |

| Del Norte | 4 miles | 4 miles | 17 miles | 46 miles |

| Humboldt | 3 miles | 50 miles | 9 miles | 92 miles |

| Mendocino | 54 miles | 25 miles | 7 miles | 41 miles |

| Sonoma | 26 miles | 7 miles | 4 miles | 25 miles |

| Marin | 17 miles | 9 miles | 66 miles | 58 miles |

| San Francisco | – | – | 2 miles | 9 miles |

| San Mateo | 21 miles | 14 miles | 33 miles | 18 miles |

| Santa Cruz | 6 miles | 20 miles | 10 miles | 7 miles |

| Monterey | 22 miles | 20 miles | 53 miles | 34 miles |

| San Luis Obispo | – | 44 miles | 7 miles | 43 miles |

| Santa Barbara | 37 miles | 31 miles | 3 miles | 17 miles |

| Ventura | 21 miles | – | 6 miles | 25 miles |

| Los Angeles | 22 miles | 5 miles | 25 miles | 34 miles |

| Orange | 11 miles | 3 miles | 3 miles | 28 miles |

| San Diego | 1 miles | 37 miles | – | 71 miles |

| TOTAL | 245 miles | 269 miles | 245 miles | 548 miles |

In summary, the report finds that of the CCT’s 1,300-mile projected length, about 40% is “adequate”, and another 40% is “inadequate” but runs on public land or along public highway corridors. For the remaining 20% of the trail’s length, acquisition of land has to be planned. From this, it was estimated that completing the trail will cost $668,350,000.

Importantly, as the report emphasizes, this amount must be considered in a larger context. No doubt, the parcels of land acquired will be often much larger than that needed just for the trail, and thus the likely costs higher. On the other hand, this land includes some of California’s most treasured terrain, either in terms of scenic or environmental value. In some cases, such land may be gifted to the state. In others, the fact that the CCT will be on a larger parcel will be an additional reason for acquiring it as parkland.

Although many persons will point out that the current rapid growth of California’s population justifies additional acquisition of public lands for recreation and environmental protection, others may voice concern that maintenance of public facilities is costly, and the CCT, once completed, will require maintenance. On the other hand, because most of the trail will be on park lands, the incremental cost of maintaining the trail will be small. Further, by involvement of volunteers and non-profit organizations such as done in Caltrans’ Adopt-a-Highway program or for the Appalachian Trail, which runs 1,800 through states on the eastern seaboard, the costs of both building and maintenance can be reduced.

Pros and Cons

Of course there will be many challenges to completing the CCT, just as there have been challenges in providing the Coastal Trail that we enjoy today. And as well, there are extended benefits to be derived from the trail’s completion. The SB 908 report gives considerable space to discussing these; considerations that can only be briefly recounted here.

One of the greatest challenges is to make sure that the trail positively serves the fragile environment of the coast. There are the nesting places of endangered species, such as the least tern, fragile tide pools, beaches visited by elephant seals to bear and raise their pups, and areas of sensitive vegetation. Impact on these niches can be kept at a minimum by using the trail to channel visitors away from the most sensitive sites, and to bring visitors within sight of others to inform them about the complex shoreline ecosystem. There are abundant examples that show that with education comes respect and protection.

Other challenges relate to private and quasi-public ownership of lands along the shoreline. One particularly contentious issue grows from the instances where structures have been built too close to the shoreline, and they are then threatened by the force of the ocean. Often armoring and revetments have been constructed and they have an adverse effect, fixing the shoreline artificially so that the beach is narrowed, in some cases to nothing. A second problem arises where development exists in an unbroken line adjacent to the beach. In the first instance, the development restricts public access along the beach—so-called lateral access—and in the second instance, it prevents vertical access from public roads to the shoreline. These challenges can be met by the acquisition of land along the shoreline, and by modest changes in the laws as they relate to armoring the shoreline.

Completing the trail will also require cooperation among many agencies and individuals. State and community agencies, Federal agencies and particularly quasi-pubic land-holders such as the military and railroads will have to maintain communications and work together to find ways to increase access along the coastline. Similar, building and maintaining the trail will require the cooperation and good will of many different interest groups—hikers, bikers and equestrians, environmentalists and so on.

The benefits of completing the trail cannot be understated.

The completion of a Coastal Trail, running continuously from Oregon to Mexico, would contribute to our quality of life in terms of:

- recreation

- access to the shoreline and its extraordinary scenic and natural surroundings

- encouragement of non-motorized transportation.

These will benefit both our mental and physical health. These virtues are not abstract but can be documented in such observations as that Americans spent $213 million on hiking boots in 2000, $284 million on backpacks, $78 million on tents and $86 million on sleeping bags, according to the American Hiking Society; and in a 2002 survey of potential home purchasers conducted by the American Association of Homebuilders, recreational trails were described as the second most important community amenity.

The CCT will have a beneficial environmental effect, both directly in procuring a natural corridor along the coast and indirectly by promoting the educational benefits derived from broadened public access to the shoreline. And in-so-far as the guidelines call for developing connections to inland population centers, it will bring such advantages to those communities.

And finally, the completion of the trail would have significant economic benefits given that Californiais already the most visited state in the nation, and outdoor recreation—and particularly walking—are high among the visitors’ recreational choices. “In the rural North Coast, where traditional resource dependent economies are in decline, scenic and open space values are high and on tourism is on the rise.” [And] “In the more urban coastal communities of central and southern California, public beaches and scenic open space enhance the quality of residential life and help to provide a competitive edge in the effort to attract new employers. The commercial tourism industry in these areas, already a strong component of the regional economy, is also strengthened by continuing public investment in accessible recreational amenities.”

Completing the CCT will have lasting value for California; the costs of accomplishing this are reasonable, and the benefits manifest.